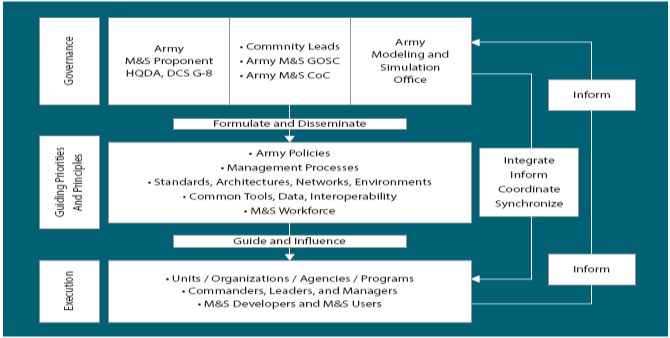

In this article, I summarize Air Force Models and Simulations (M&S) policy initiatives and M&S enhancements for decision support analytics for warfighters and acquisitions. The policy initiatives include implementing an M&S governance structure, instantiating a study governance oversight, and evaluating the analytic capability across the Air Force. The various M&S enhancements span the levels from engagement, through mission area and campaign, to enterprise. The enhancements are all directed at improving the range and scope of decisions that we can support for operators, logistics, planners, and programmers.

The Air Force is taking various actions to improve M&S that are used for decision support. The following are my personal views on various initiatives from my perch in the operations research unit of the Air Staff. The advantage of these being my personal views is I can be much more candid and include my suggestions on the direction that the Air Force should precede. Another advantage is some of you may not agree with my perspective; any disagreement is a starting point on a dialog on the best approach for the Air Force. The disadvantage is that since these are preliminary, rather than coordinated and official statements, these may not be the direction that the Air Force actually pursues on these matters.

The first section presents a few definitions to set the stage for the remainder of the article. The next section describes organizational initiatives to make the Air Force analytic community more effective and efficient. In general, these policies and programs are intended to increase our ability to share data, models, and results. The subsequent section describes actions to improve specific M&S tools, whether models or simulations, for better analytic capability.

The following definitions, at least how I am using terms, should help clarify this discussion. Modeling and simulation is not well defined. The two terms are not even grammatically equivalent. In this article, I propose and use the following fundamental definitions:

- A model is representation or pattern, with the subset of analytic models are mathematical, symbolic, or algorithmic representations of reality or a system.

- A simulation is a representation of a system with entities or variables that change states over time.

With these definitions, we can classify various analysis tools as a model, simulation, both, or neither. A military exercise with combat units is a simulation, but not a model. Similarly, a regression equation, even with time as a variable, is a model and not a simulation because no entities change state. Any simulation that runs on a computer is also a model. See Table 1 for examples of models and simulations. Finally, I define M&S as the collection of analytic models and simulations.

Table 1. Example of Models and SimulationThe Live, Virtual, and Constructive (LVC) scheme is not comprehensive because LVC is used to describe how individuals are portrayed. Pew and Mavor (1998) and Zacharias, MacMillan and Van Hemel (2008) present summaries on modeling human behavior. While some use “constructive” to describe any model that is not live or virtual, DoD (2015) defines constructive as simulating people, which implies their behavior is modeled. Most of our analytic models for decision support do not represent individual behavior at all. Hence, constructive simulations are only a subset of the analytic models and simulations.

Table 1. Example of Models and SimulationThe Live, Virtual, and Constructive (LVC) scheme is not comprehensive because LVC is used to describe how individuals are portrayed. Pew and Mavor (1998) and Zacharias, MacMillan and Van Hemel (2008) present summaries on modeling human behavior. While some use “constructive” to describe any model that is not live or virtual, DoD (2015) defines constructive as simulating people, which implies their behavior is modeled. Most of our analytic models for decision support do not represent individual behavior at all. Hence, constructive simulations are only a subset of the analytic models and simulations.

I view that there is a spectrum from analyst-intensive M&S to hardware-intensive simulations, as shown in Table 2. Some in this community may wonder why I am using the adjective “analyst-intensive” versus “decision support;” I find decision support is not a meaningful discriminator as everyone in this field is supporting some decision-making process. Some apply the term simulators, rather than simulations, to the real-time realistic system representations that are used to train operators. Simulators are distinct from analytic simulations; hence, simulations and simulators are appropriate for different uses and require different management approaches. However, other hardware-in-the-loop simulations are used to develop operational procedures and evaluate potential new technologies; these are much closer to the use of analytic simulations. In fact, we mention in this article using the same system models in the analytic and virtual simulations. I want to be clear that no one type of model or simulation is better than another type; each of these simulation approaches has appropriate applications.

Wargames are also used for decision support. I define wargames as having humans, on competing sides, making inputs during play in a postulated military conflict, without actual military forces or real equipment involved (Perla and Branting 1986). Since no equipment is used, wargames are distinct from live or virtual simulations. Because wargames are played in time, they are always simulations. Most wargames are adjudicated by a “white cell,” which may or may not use models or computer simulations. I recommend, when possible, a technical evaluation of outcomes. The focus of wargames is on the interaction of competing leaders making decisions for their organizations; hence wargames are particularly useful in evaluating strategy, operational concepts, and the associated decisions space, such as devising an appropriate strategy and related courses of action in a scenario.

Table 2. Spectrum from Analytic-Intensive to Hardware-Intensive SimulationsThe Office of Secretary of Defense (OSD) and the Joint Staff are revamping Support for Strategic Analysis (SSA). The Air Force and the other services are participating. They are searching how to build scenario baselines faster and an approach to support our decision makers through the integration of wargame results and analytic products. Where wargames are better at testing human organization decisions, I contend analytic approaches are better suited for evaluating the effectiveness of systems, including new technologies. Wargames and analysis should interface. For example, a strategist might use a wargame to assist in developing a strategy and types of forces desired in a scenario, and then analysts might use those results to build an analytic baseline for that scenario to evaluate various force mixes. Like the hierarchy of analytic levels, depicted in Figure 1, we may need to develop scenario levels or degrees to indicate their analytic rigor. We also need a better categorization of wargames.

Table 2. Spectrum from Analytic-Intensive to Hardware-Intensive SimulationsThe Office of Secretary of Defense (OSD) and the Joint Staff are revamping Support for Strategic Analysis (SSA). The Air Force and the other services are participating. They are searching how to build scenario baselines faster and an approach to support our decision makers through the integration of wargame results and analytic products. Where wargames are better at testing human organization decisions, I contend analytic approaches are better suited for evaluating the effectiveness of systems, including new technologies. Wargames and analysis should interface. For example, a strategist might use a wargame to assist in developing a strategy and types of forces desired in a scenario, and then analysts might use those results to build an analytic baseline for that scenario to evaluate various force mixes. Like the hierarchy of analytic levels, depicted in Figure 1, we may need to develop scenario levels or degrees to indicate their analytic rigor. We also need a better categorization of wargames.

In continuing to be bold – and for the sake of prompting thoughtful dialogue – I propose the following definitions of analyses, studies, and assessments. I will use the adjective analytic to distinguish from the wide application of these terms that are distinct from applications of M&S. The Institute for Operations Research and Managment Science (INFORMS) (2015) states: “Analytics is the scientific process of transforming data into insight for making better decisions”. This transformation process often starts with raw data, such as system performance specifications, as input into one or several system models and examines the modeled outputs along with sensitivities. The process may continue with those results being input into another model or a series of models, perhaps at different resolution levels. Hence, an analytic analysis uses models or simulations to evaluate the impacts of alternative decisions. An analytic study is more extensive and more formal than an analysis, although there is no agreed upon division between these two. Generally, I expect that a study has a formal plan, final report, and encompasses a level of resources of more than one full-time equivalent, such as at least four analysts for three months. An analysis or study does not tell the decision maker the appropriate decision; rather it describes the impact of various choices. A study rarely encompasses all the variables or aspects that a decision maker should consider—certainly not on complex defense acquisition decisions that affect the industrial base and many political constituents. That said, once a decision maker has selected a direction, more focused analysis on implementing that choice is often prudent. Finally, an analytic assessment is a collection of metrics and measures to indicate the state of a system, without being focused on a particular decision (Clark and Cook 2008). With these definitions, I can frame the rest of this discussion.

The focus of this article is on analytic M&S, which are used to support decision makers. These analyses are categorized into levels based on the questions and issues being investigated. A widely-used hierarchy is shown in Figure 1. The large base indicates many models and simulations exist and are needed at the levels with more resolution; however, analysts use fewer more-encompassing models at more aggregate levels as they move up the pyramid depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Common Analytic M&S HierarchyIndividual models or simulations may be characterized by the issues and questions that they are designed to address. Figure 2 shows a hierarchy depicting how scope and resolution of any particular model differs, depending on the intended level of analysis. Even with increased speed of computers, use of these levels makes sense since they enable (Gallagher, Caswell, et al. 2014):

Figure 1 – Common Analytic M&S HierarchyIndividual models or simulations may be characterized by the issues and questions that they are designed to address. Figure 2 shows a hierarchy depicting how scope and resolution of any particular model differs, depending on the intended level of analysis. Even with increased speed of computers, use of these levels makes sense since they enable (Gallagher, Caswell, et al. 2014):

- Modeled aspects to be relevant to the issue or question under investigation,

- Wider applicability of results (consistent with data inputs of the models),

- An efficient search of the decision-space, and

- Focused and manageable data requirements for any particular analysis.

Analysis insights and results flow up and down the analysis hierarchy. We are documenting the general process to tune models or simulations across the levels of analysis.

Figure 2 – Conflict M&S Hierarchy (Gallagher, Caswell, et al. 2014)In the following section, we discuss M&S governance initiatives, and, in the subsequent section, I describe some of our analytic M&S enhancements.

Figure 2 – Conflict M&S Hierarchy (Gallagher, Caswell, et al. 2014)In the following section, we discuss M&S governance initiatives, and, in the subsequent section, I describe some of our analytic M&S enhancements.